This research report was designed by Stop Funding Hate and Ethical Consumer to address the problem of subtle hate in UK media coverage of migration and to explore ways of addressing it.

October 4th 2022

October 4th 2022

The research looked at subtle forms and drivers of hate in UK media coverage of migration. It sought to answer three main questions:

For this report we undertook a literature review and drew on key input from academics and expert practitioners.

Anti-migrant hate in the UK media specifically has been well documented. In 2015, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, urged British authorities and media to take steps to curb incitement to hatred by tabloid newspapers, after decades of “sustained and unrestrained anti-foreigner abuse.”(i) The call followed publication of an article in the Sun newspaper calling migrants “cockroaches”. The UN noted:

“the Sun article was simply one of the more extreme examples of thousands of anti-foreigner articles that have appeared in UK tabloids over the past two decades. Asylum seekers and migrants have been linked to rape, murder, disease, theft, and almost every conceivable crime and misdemeanour in front-page articles and two-page spreads, in cartoons, editorials, even on the sports pages of almost all the UK’s national tabloid newspapers.”(ii)

Building on the statements, in 2016 the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance criticized UK media, particularly the UK tabloid press, over its “offensive, discriminatory and provocative terminology” including on migration.(iii)

In recent years, several UK newspapers have publicly claimed to have cleaned up their act when it comes to coverage of migration. Articles referring to refugees as “cockroaches” and suggesting they should be met with gunboats in mainstream media appear to be a thing of the past. Two national newspapers have publicly reviewed their policies in relation to reporting on migration.(iv) The new editor at the Daily Express publicly reformed its approach, after the paper published 70 anti-migrant front pages in 2016 and was targeted by Stop Funding Hate.(v)

As a result of these changes, vitriolic and unequivocally hateful coverage on migration appears less common, and there seems to have been a significant reduction in attention on UK media from international society.

Yet, Stop Funding Hate’s consultations with partners have revealed ongoing concern about the prevalence of more subtle anti-migrant narratives within the UK media. One particular worry raised is that such narratives may, in some cases, have a greater impact on public perceptions than more obviously problematic headlines.

Many newspapers continue to publish subtle, insidious forms of hateful anti-migrant reporting. Subtle forms and drivers of hate take many forms. Media has repeatedly and disproportionately associated the migrant community with child abuse, grooming and criminality.(vi) It has published unevidenced and uncontested figures on migrant numbers (vii) and repeatedly referred to new arrivals as a ‘surge’.(viii) It has obsessed over birth rates, dangerously echoing conspiracy theories that the white British population is about to be usurped.(ix)

The issue of anti-migrant sentiment clearly has not gone away. In 2020, Clarke wrote: “official and media discourse has fed into wide-spread, normalised anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiment amongst the general public.”(x) Where research has looked at ongoing media bias, it has continued to identify instances of anti-migrant rhetoric. For example, the Centre for Media Monitoring has identified several articles from 2018-2020 where anti-migrant reporting intersects with Islamophobia.(xi)

For this report, Ethical Consumer interviewed ten experts on hate and migration. Across the board, interviewees expressed serious concerns about the proliferation and impact of more subtle forms of anti-migrant hate in UK media. Interviewees stated that it had a serious cumulative impact on both readers and migrants over time. As interviewees suggested, anti-migrant narratives can give “permission” for readers to hold or act on prejudice or more vitriolic hateful views. Media narratives can therefore sanction hate in wider society. Yet, such subtle forms and drivers of hate may be “normalised and embedded” in our society, often making them more difficult to recognise and identify.

Indeed, recognition of anti-migrant hate is globally several steps behind understanding of other areas. The treatment of undocumented migrants exists as a “blind spot” and the “last frontier” for tackling hate in our societies, according to Pia Oberoi, Senior Advisor on Migration and Human Rights for the Asia Pacific Region for the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner on Human Rights.

Anti-migrant hate impacts many in our society. It affects those who are newly arrived or undocumented, asylum seekers and migrants, but it also impacts those who are perceived or racialised as migrants regardless of migration status. Muslim, Irish Traveller, Eastern European and other communities have been persistent targets of anti-migrant hate – both subtle and vitriolic. Understanding the intersection between anti-migrant and other forms of prejudice is therefore crucial for combatting its effects.

In recent years, the harms associated with ‘everyday hate’ and ‘microaggressions' have been widely evidenced. Victims of these kinds of hate are more likely to experience depression and the exacerbation of existing trauma. They are more likely to withdraw from everyday life, avoid certain public spaces and / or feel forced to conceal their nationality or asylum seeker status.

While limited research has specifically studied the impacts of subtle hate in the media, much is known about the symbiotic relationship between media narratives, public prejudice and harmful policy stances. As interviewees suggested, anti-migrant narratives can give “permission” for readers to hold or act on prejudice or more vitriolic hateful views. Media narratives sanction hate in wider society.

It is also clear that the hate speech against refugees and migrants can manifest itself in serious acts of violence. This can be about people fearing for their own safety and not just about being made to feel unwelcome. Indeed, in the main report, we explore a couple of academic works, such as Allport's Scale of Prejudice, which situates subtle forms of hate speech at the beginning of an erosion of values that can end in serious violence and even genocide. (xii)

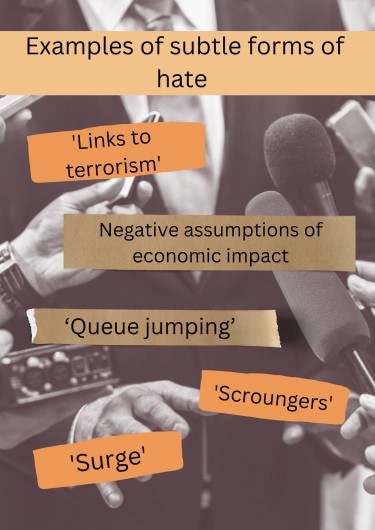

Subtle hate refers to coded or implied “hostile, derogatory or negative… slights and insults” (xiii) against migrant individuals or groups. It is usually characterised by content that constructs migrants as a threat / problem / unwelcome / to be scared of, without stating it in explicit terms. Drivers of hate spread, encourage, or sanction such views in wider society.

Both subtle forms and drivers of hate can manifest in multiple ways. Due to their covert and nuanced nature, subtle forms and drivers of hate can be difficult to identify as isolated articles or headlines. They are instead characterised by repetition, sheer volume, or disproportionality of focus on an issue.

According to interviewees, for example, the UK media repeatedly makes unevidenced links between migration and overwhelmed public services. It makes frequent generalisations about Muslim migrants oppressing women in their communities. It disproportionately shows Black male migrants waiting in queues, jumping out of lorries or climbing over fences. While individual instances of these kinds of reporting may appear neutral, “a sustained approach has a very different impact” and can clearly produce an anti-migrant narrative over time.

As part of the research we undertook a literature review and also tried to collect together all the examples we could find of subtle hate. There is a 62 page Appendix to the main report which lists examples and also looks at whether they fall into categories which help us to understand them. Working through this list and talking to specialists in this space led us to identify six key components of hateful reporting, beyond explicit vitriolic hate.

Categorising subtle forms and drivers of hate is crucial for building public understanding. As one interviewee pointed out: “If people don’t have words for it, it’s not a thing. Giving a narrative casing for subtle forms of hate is unbelievably helpful.” (Harriet Kingaby, Conscious Advertising Network).

The table below describes each category and summarises some of the examples and tropes that might be found under each one. Just one newspaper article could fall under multiple categories. The main report proposes how the categories could be developed further and used for monitoring, education and building evidence of sustained anti-migrant reporting.

| Overarching category | Subcategories | Examples of speech |

|---|---|---|

| Vitriolic hate Explicit forms of hate, including incitement (This is unlikely to be subtle) |

Epithets Incitement to violence Incitement to discrimination |

Dirty |

| ‘Threat’ construction The portrayal of migrants as a threat, and the construction of an ‘in-group’ and ‘out-group’ |

Demonisation “Accusations in a mirror” Construction of ‘symbolic threat’ Construction of ‘realistic threat’ Construction of in-groups and out-groups Assumption of incompatibility Moral panic Portrayal of migration in terminology of war Conspiracy theory Misogyny in reporting |

Bogus claims Scroungers Links to terrorism Criminals ‘Islamic Europe’ Cultural threat ‘Cricket test’ Negative assumptions of economic impact Incompatibility Violence Great Replacement Conspiracy Theory Focus on ‘birth rates’ ‘Refusal to assimilate’ Threat to white women Generalisations about oppression of women from migrant group Irrelevant emphasis on nationality in reports on sexual assault References to ‘lefty lawyers’ undermining democracy and / or British values Association with FGM ‘Queue jumping’ Bringing disease |

| Fakes, inaccuracy and misrepresentation Use of inaccurate and / or unevidenced claims |

Toxic misinformation |

Links to terrorism Threats to law and order Bogus claims Criminals Illegal migrants Negative assumptions of economic impact Unevidenced links between migration and overstretched public services |

| Selective reporting Omitting certain issues around migration or giving disproportionate prominence to other issues |

Selective reporting Lack of due prominence |

No migrant voice No migration histories No Muslim voice No coverage of women migrants Imagery that solely focuses on male migrants Selective quoting of third-party reports Irrelevant reference to race etc |

| Generalisations Making a general assumption across a group based on inferences of individual cases |

Generalisation Stereotyping |

Around Muslim belief/behaviour Hard-line beliefs Poor animal welfare tropes |

| Dehumanisation Depriving of human qualities |

Dehumanisation Massification Demonisation of humanitarian assistance |

Mass migration Surge Swarm Flood |

| Intersectional prejudice ‘Borrowing’ from other forms of prejudice to create a prejudicial view of migrants. Toxic amplification of multiple forms of hate and discrimination. |

Intersectional prejudice Prejudicial hierarchies Construction of ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ (regardless of migration status) |

Good migrants (e.g. NHS/white) and bad migrants (criminal, Black) Muslim plot theories |

All interviewees were asked about the feasibility of and techniques for communicating more subtle forms and drivers of hate to the UK public. This topic was discussed in depth with those from the Anti-Semitism Policy Trust, Stop Hate UK and the Conscious Advertising Network, to learn from their experiences explaining anti-Semitism, conducting counter narrative work, and challenging both hate and climate misinformation respectively.

Overall, interviewees expressed mixed opinions on the feasibility of communicating subtle forms and drivers of anti-migrant hate. While some expressed confidence that it could be done, others suggested that it was “very difficult”. “Nuance and subtlety is lost in the public, political, media spaces… it’s a massive challenge trying to talk to people about these subtle ways.” (Chris Allen)

In total, we collected together ten key approaches that interviewees thought were important. Each of these elements is discussed in a separate section in the main report.

Most interviewees referenced a range of the above approaches rather than suggesting one particular tactic, and Harriet Kingaby and Alex Murray specifically stated “telling the story has lots of components”. They suggested that persuading advertisers required combining, for example, statistics from think tanks, real life stories of impacts and incidents that have got that particular corporation to the table.

Clearly, subtle forms and drivers of anti-migrant hate in UK media need addressing, but these forms necessarily fall outside of content regulation and legislation. Civil society therefore holds a crucial role in addressing this area and for communicating more subtle forms and drivers of hate to the UK public.

Stop Funding Hate is well placed to campaign for change. Interviewees referenced the previous successes of the campaign; the significance of its tactics to economically incentivise change; the importance of its commercial angle in the context of an “unfit for purpose complaints body”; and the way in which Stop Funding Hate was able to make a material argument that cut through toxic debates around ‘political correctness’ and ‘woke wars’.

Many interviewees also referenced the particular difficulties of launching a campaign of this kind at this time – from the hostile political environment around migration to the toxic social media backlash against ‘snowflakes’ and ‘culture wars’. However, even where interviewees expressed concerns or emphasised the challenges of this kind of campaign, they suggested that “it’s absolutely the right place for Stop Funding Hate to be.”

Interviewees identified crucial components for a campaign of this kind, each of which is explored in more detail in the main report. Key components are summarised below:

For the public to support a campaign of this kind, it needs to understand what subtle hate is and what it looks like, as well as its impact and trends. This report highlights key techniques that could be used to build media literacy around subtle hate. Approaches include comparing hateful and legitimate examples of migration reporting, explaining the history of particular tropes and stereotypes, educating about how discourse can dehumanize a group identity over time and providing facts and figures on the prevalence of subtle prejudiced views in society as a whole.

Interviewees repeatedly emphasised the importance of demonstrating a “sustained approach” by media outlets over time. Building this body of evidence was highlighted as crucial to both ensuring public support and persuading advertisers. Interviewees mentioned a variety of approaches to demonstrating trends, patterns and volume. Several interviewees discussed more formal approaches such as concerted monitoring and civil society reporting, while others suggested more informal techniques such as using images to demonstrate repetition.

Evidencing the cumulative effect of subtle media hate was also highlighted as crucial to gaining public support and convincing advertisers. As discussed in the report, a growing body of evidence shows the serious impacts of subtle hate on victims over time, but little research has yet focused on the specific effects of media outlets.

Equally important is supporting members of the migrant community to tell their personal stories. This approach – providing an emotional appeal to action – draws on findings from the counter-narrative movement that stories rather than facts can change public views. It also supports the necessary work of rehumanising migrants, who have been consistently dehumanised by the press.

The responsibility of media in tackling both hate and bias has been recognised internationally, and the UN and other intergovernmental or civil society organisations have provided guidance on best practice for migration reporting.

More recently, international and national guidelines – from The UN Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (xiv) to the UK Government Online Advertising Programme’s Taxonomy of Industry Harms (xv) – have also recognised the role of advertisers. As the UN Compact says, “in full respect for the freedom of the media", advertisers should avoid providing funds to media outlets that systematically promote intolerance, xenophobia, racism and other forms of discrimination towards migrants.” (xvi) Subtle hate is a crucial element of systematic and sustained promotion of intolerance by media outlets.

In recent years, a growing number of advertisers in the UK have also recognised the brand risks associated with, and their responsibility to avoid, funding hateful reporting. Advertisers have withdrawn funding from a number of media outlets and made long-term commitments to better practice through membership of the Conscious Advertising Network. Yet, subtle forms and drivers of hate have remained largely unaddressed.

Whilst it’s impossible to conclusively say whether campaigning on subtle forms of hate would directly succeed in persuading advertisers to withdraw funding from subtle hate and drivers of hate, the report concludes that a Stop Funding Hate campaign on subtle forms of hate could play a significant role as part of a wider “ecosystem” of different civil society interventions. Useful additional work in this area would include:

i) ‘UN rights chief urges UK to curb tabloid hate speech, end ‘decades of abuse’ targeting migrants’, UN News, (24th April 2015). Accessed 8th March 2022. https://news.un.org/en/story/2015/04/496892

ii) ‘UN rights chief urges UK to curb tabloid hate speech, end ‘decades of abuse’ targeting migrants’, UN News, (24th April 2015). Accessed 8th March 2022. https://news.un.org/en/story/2015/04/496892

iii) European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance, ‘ECRI Report on the United Kingdom’, Council of Europe, 5th Monitoring Cycle, (4th October 2016). https://rm.coe.int/fifth-report-on-the-united-kingdom/16808b5758

iv) ‘How to Challenge Media Hate’, Ethical Consumer, (21st November 2021). Accessed 8th March 2022. https://www.ethicalconsumer.org/ethicalcampaigns/stop-funding-hate

v) McCarthy, John, ‘After axing anti-immigration stories, The Daily Express hopes for advertiser reappraisal’, The Drum, (7th August 2019). Accessed 8th march 2022. https://www.thedrum.com/news/2019/08/07/after-axing-anti-immigration-stories-the-daily-express-hopes-advertiser-reappraisal

vi) E.g. Robinson, James, ‘Afghan migrant who 'drugged, raped and murdered 13-year-old girl' then crossed the Channel WILL be extradited to Austria to stand trial as British court rejects his bid to remain in the UK’ in Mail Online, (12th January 2022). Accessed online, 20th May 2022. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10394347/Afghan-migrant-drugged-raped-murdered-13-year-old-girl-sent-Austria.html

vii) E.g. Walters, Jack, ‘‘Rwanda about to rebound’ Farage warns 100k migrants to arrive unless Brexit is completed’, in Daily Express, (5th May 2022). Accessed online, 20th May 2022. https://www.express.co.uk/news/politics/1605527/nigel-farage-brexit-ukip-rwanda-immigration-channel-crossing-latest-news-ont

viii) E.g. Maddox, David, ‘Illegal migrants surge caused by people smugglers claiming there is a rush to avoid Rwanda’ in Daily Express (4th May 2022). Accessed online, 20th May 2022. https://www.express.co.uk/news/politics/1604876/immigration-people-smugglers-rwanda

ix) E.g. Robinson, Alexander, ‘Muslim population in parts of Europe could TRIPLE by 2050: New study predicts migration and birth rates will lead to dramatic rise in numbers across continent’ in Mail Online (29th November 2017). Accessed online, 20th May 2022. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5130617/Study-Europes-Muslim-population-grow-migration-not.html; ‘Fortress Europe: As Islam Expands, Should the US Imitate the 'Christian' Continent?’ in Christianity Today, (3rd June 2021). Accessed online, 16th May 2022. https://www.christianitytoday.com/news/2021/june/europe-muslim-population-christian-islamophobia-austria.html; and Betham, Martin, ‘Migration to be main driver of UK population growth as birth rate slows’ in Evening Standard (13th January 2022). Accessed online, 20th May 2022. https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/migration-uk-population-growth-birth-rate-slows-b976439.html

x) Clarke, Amy L. ‘Lost Voices’: The targeted hostility experienced by new arrivals. Diss. University of Leicester, 2020.

xi) Hanif, Faisal, ‘British Media’s Coverage of Muslims and Islam (2018-2020)’, Centre for Media Monitoring, (November 2021). Accessed 8th March 2022. https://cfmm.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/CfMM-Annual-Report-2018-2020-digital.pdf

xii) See Section 3.4 in the main report.

xiii) Sue, Derald Wing. Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. John Wiley & Sons, 2010. p.5

xiv) ‘Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration’, United Nations Human Rights - Office of the High Commissioner, (13th July 2018). https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/sites/default/files/180713_agreed_outcome_global_compact_for_migration.pdf

xv) ‘Consultation on reviewing the regulatory framework for online advertising in the UK: The Online Advertising Programme’, Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (March 2022). Accessed online 20th May 2022. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1061202/21012022_Online_Advertising_Programme_Impact_Assessment_PUB__Web_accessible_.pdf

xvi) ‘Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration’, United Nations Human Rights - Office of the High Commissioner, (13th July 2018). https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/sites/default/files/180713_agreed_outcome_global_compact_for_migration.pdf

This report was researched and compiled by Clare Carlile and Rob Harrison at Ethical Consumer between February and July 2022. Specialists interviewed for and helping with this report include:

This research report was made possible thanks to the support of Paul Hamlyn Foundation.