Research findings

Company and brand ownership

Since Ethical Consumer rates companies mainly by the policies and conduct of their ultimate parent company, the research started with a dive into who owned the various brands.

As expected, several well-known brands belonged to lesser known parent companies and some of the large companies owned competing brands that they market separately.

AB Electrolux, for example, was found to also make AEG and Zanussi, and Whirlpool owns Hotpoint and Indesit. Siemens’ white goods are actually made by a company fully owned by Bosch, and Philips televisions now come from an independent Chinese company called TPV Technology.

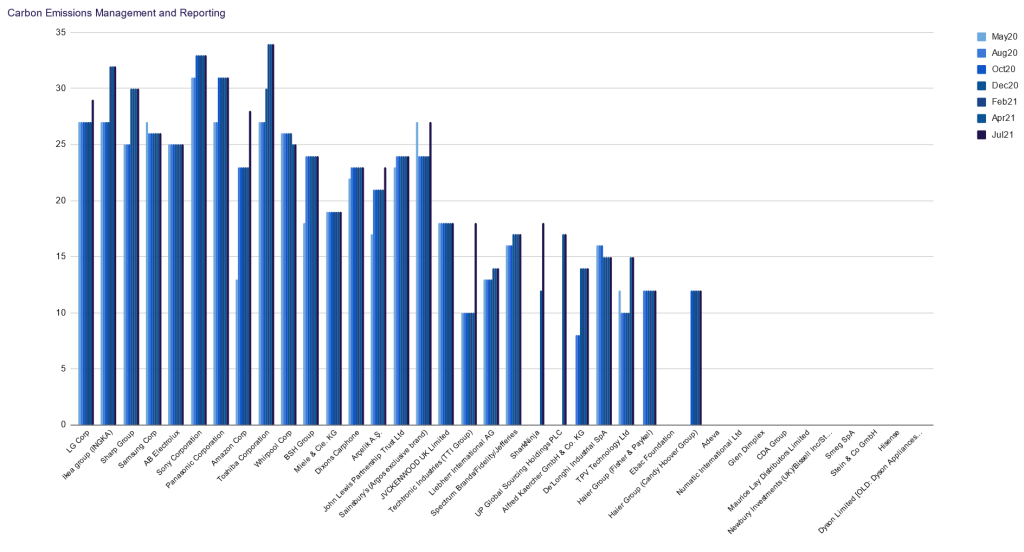

Carbon management and reporting (Max 35 points)

In 2020, Ethical Consumer introduced a new carbon management and reporting category, which was in part based on what we found out about current standards of reporting during this project. To get a thorough idea of what was happening in this field, we collected a wide range of data:

- Did the company report emissions at least annually?

- Were carbon data independently verified?

- Was a widely recognised independent reporting standard used?

- Were all relevant greenhouse gases reported?

- Were previous year’s carbon emissions reported alongside the current year?

- Were absolute emissions as well as an intensity ratio reported?

- Did reporting cover all emissions a company is responsible for up to and including those in its value chain to at least first tier suppliers (‘scope 3’)?

- Did the company have a decarbonisation target at least in line with international agreements?

- Did carbon mitigation and any offsetting strategies use credible named and geographically specific projects only?

Companies clearly started taking carbon reporting more seriously during the reporting period. In the first report, 22 did not report anything on carbon emissions, and only Sony scored 30 or more out of 35. In the final report the number of reporting companies had gone up from 20 to 25, and scores of 30 or more came from Toshiba (34), Sony (33), IKEA (32), Panasonic (31) and Sharp (30).

One of the aspects we were most interested in was the reporting of carbon emissions from companies’ supply chains (‘scope 3’ or ‘indirect emissions’). We were looking specifically for emissions from supplying factories, transport to and from factories or retailers, and product lifecycle emissions. For companies that produce physical goods, this is the bulk of their carbon footprint and can easily amount to 90% of a company’s impact. Accounting for scope 3 emissions is an important step forward in calculating the real carbon cost of a company’s operations.

Unfortunately, the number of companies that reported some or all of these scope 3 emissions only went up by 1 throughout the reporting period, from 7 to 8, although the importance of dealing with supply chain emissions became a more prominent theme in sustainability reports published towards the end of the project period. However, the majority (28 or 64%) failed to demonstrate that they had grasped the necessity to take decisive action.

By the end of the project, 14 companies had a carbon reduction target in line with international agreements. This had been 6 at the start, so this was a significant improvement. In recent sustainability reports, many companies that already report carbon emissions have started to set carbon reduction targets approved by the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) or stated they were working with SBTi to formulate them. SBTi considers targets ‘science-based’ if they are “in line with what the latest climate science deems necessary to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement – limiting global warming to well-below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C”.

We also wanted to explore how companies used ‘offsetting’ in their carbon emissions calculations. ‘Creative carbon accounting’ tends to rely on this controversial practice, which allows companies to fund projects designed to reduce carbon emissions and then subtract these carbon reductions from their own emissions figure.

In our research we found that only IKEA and Sharp relied on the best type – carbon mitigation strategies that directly addressed their own emissions. Other companies did not (fully) explain what type of projects they funded or used strategies such as buying carbon credits. A few traded carbon credits received for carbon-friendly product lines for discounts on carbon emissions from other parts of their production process.